Ghana Empire

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Ghana Empire or Wagadou Empire (existed c. 790-1076) was located in what is now southeastern Mauritania, and Western Mali. It first began in the eighth century, when a dramatic shift in the economy of the Sahel area south of the Sahara allowed more centralized states to form. The introduction of the camel, which preceded Muslims and Islam by several centuries, brought about a gradual change in trade, and for the first time, the extensive gold, ivory, and salt resources of the region could be sent north and east to population centers in North Africa, the Middle East and Europe in exchange for manufactured goods.

The Empire grew rich from the trans-Saharan trade in gold and salt. This trade produced an increasing surplus, allowing for larger urban centres. It also encouraged territorial expansion to gain control over the lucrative trade routes.

The first written mention of the kingdom comes soon after it was contacted by Sanhaja Berber traders in the eighth century. In the late ninth and early tenth centuries, there are more detailed accounts of a centralized monarchy that dominated the states in the region. The Cordoban scholar al-Bakri collected stories from a number of travelers to the region, and gave a detailed description of the kingdom in 1067. At that time it was alleged by contemporary writers that the Ghana could field an army of some 200,000 soldiers and cavalry.

Upon the death of a Ghana, he was succeeded by his sister's son (matriliny). The deceased Ghana would be buried in a large dome-roofed tomb. The religion of the kingdom involved emperor worship of the Ghana and worship of the Ougadou-Bida, a mythical water serpent of the Niger River.

Contents |

Origin

The origins of the Ghana Empire have been controversial, and theories about them have changed over the years. The earliest disucssions of their origins are found in the Sudanese chronicles of Mahumd Kati and Abdirahman as-Sadi. According to Kati's Tarikh al-Fettashin a section probably composed by the author around 1580, but citing the authority of the chief judge of Massina, Ida al-Massini who lived somewhat earlier, twenty kings ruled Ghana before the advent of the Prophet, and the empire extended until the century after the prophet (ie c. 822 CE).[1] In addressing the rulers origin, the Tarikh al-Fettash, provides three different opinions, one that they were Wa'kuri (ie Soninke), another that they were Wangara (ie. Mande), and a third that they were Sanhaja, a desert tribe of Amazinghy (Berbers), an interpretation which al-Kati favored in view of the fact that their genealogies linked them to this group, and adds "What is certain is that they were not blacks (sudan).[2] As-Sadi (who wrote in the 1660s), for his part, only notes that they were "white" (bidan, which in the Sudan is as much a genealogical as racial term) and did not know their exact origin. He says that 22 kings ruled before the Hijra and 22 after.[3]

French colonial officials, notably the erudite but prejudiced Maurice Delafosse, concluded that Ghana had been founded by some sort of nomadic group from northern Africa, and linked them to European origins. While Delafosse produced a convoluted theory of an invasion by Judeo-Syrians, which he linked to the Fulbe, others took the tradition at face value and accepted simply that nomads had ruled first.[4] More recent work, for example by Nehemia Levtzion, in his classic work published in 1973, opted for a theory that had been gaining ground in the 1960s that the ultimate origins of the empire lay in the gold trade to North Africa, and that this stimulus had led to the origins of the Empire, especially as the earliest documentary sources had stressed the ruler in those days (ninth century) was of local origin and black skinned.[5]

Archaeological research was slow to enter the picture. While French archaeologists believed they had located the capital, Koumbi-Saleh in 1939, when they located extensive stone ruins in the general area given in most sources for the capital, and others argued that elaborate burials in the Niger Bend area may have been linked to the empire, it was not until 1969, when Patrick Munson excavated at Dar Tichitt in modern day Mauretania that the probability of an entirely local origin was raised.[6] The Dar Tichitt site had clearly become a complex civilization by 900 BCE and had architectural and material culture elements that seemed to match the site at Koumbi-Saleh. In more recent work in Dar Tichitt, and then in Dar Nema and Dar Walata, it has become more and more clear that as the desert advanced, the Dar Tichitt culture (which had abandoned its earliest site around 300 BCE, possibly because of pressure from desert nomads, but also because of increasing aridity) and moved southward into the still well watered areas of northern Mali. This now seems the likely history of the complex society that can be documented at Koumbi-Saleh and is associated with Ghana.

Koumbi Saleh

The empire's capital was built at Koumbi Saleh on the edge of the Sahara desert. The capital was actually two cities six miles apart connected by a six-mile road. But settlements between the cities became so dense due to the influx of people coming to trade, that they merged into one. Most of the houses were built of wood and clay, but wealthy and important residents lived in homes of wood and stone. This large metropolis of over 30,000 people remained divided after its merger forming two distinct areas within the city.

El Ghaba Section

The major part of the city was called El-Ghaba. It was protected by a stone wall and functioned as the royal and spiritual capital of the Empire. It contained a sacred grove of trees used for Soninke religious rites. It also contained the king's palace, the grandest structure in the city. There was also one mosque for visiting Muslim officials. (El-Ghaba, coincidentally or not, means "The Forest" in Arabic.)

Merchant Section

The name of the other section of the city has not been passed down. It is known that it was the center of trade and functioned as a sort of business district of the capital. It was inhabited almost entirely by Arab and Amazighy merchants. Because the majority of these merchants were Muslim, this part of the city contained more than a dozen mosques.

Economy

Both gold and salt seemed to be the dominant sources of revenue, exchanged for products such as textiles, ornaments and cloth, among other materials. Many of the hand-crafted leather goods found in old Morocco also had their origins in the empire.[7] The main centre of trade was Koumbi Saleh. The taxation system imposed by the king (or 'Ghana') required that both importers and exporters pay a percentage fee, not in currency, but in the product itself. Tax was also extended to the goldmines. In addition to the exerted influence of the king onto local regions, tribute was also received from various tributary states and chiefdoms to the empire's peripheral.[8] The introduction of the camel played a key role in Soninke success as well, allowing products and goods to be transported much more efficiently across the Sahara. These contributing factors all helped the empire remain powerful for some time, providing a rich and stable economy that was to last over several centuries.'

Government

Much testimony on ancient Ghana depended on how well disposed the king was to foreign travelers, from which the majority of information on the empire comes. Islamic writers often commented on the social-political stability of the empire based on the seemingly just actions and grandeur of the king. A Moorish nobleman who lived in Spain by the name of al-Bakri questioned merchants who visited the empire in the 11th century and wrote that the king:

Gives an audience to his people, in order to listen to their complaints and set them right…he sits in a pavilion around which stand 10 horses with gold embodied trappings. Behind the king stand 10 pages holding shields and gold mounted swords; on his right are the sons or princes of his empire, splendidly clad and with gold plaited in their hair. Before him sits the high priest, and behind the high priest sit the other priests…The doilion is guarded by dogs of an excellent breed who almost never leave the king's presence and who wear collars of gold and silver studded with bells of the same material

Decline

The empire began struggling after reaching its apex in the early 11th century. By 1059, the population density around the empire's leading cities was seriously overtaxing the region. The Sahara desert was expanding southward, threatening food supplies. While imported food was sufficient to support the population when income from trade was high, when trade faltered, this system also broke down. It has been often supposed that Ghana came under siege by the Almoravids in 1062 under the command of Abu-Bakr Ibn-Umar in an attempt to gain control of the coveted Saharan trade routes. A war was waged, said to have been justified as an act of conversion through military arms (lesser jihad) in which they were eventually successful in subduing Ghana by 1067, despite resistance by Ghana Bassi and his successor Ghana Tunka Manin. This view however, has seen general scrutiny and is disputed by some scholars as a distortion of primary sources.[9] Conrad and Fisher (1982) suggested that the notion of any Almoravid military conquest at its core is merely perpetuated folklore, while others such as Dierk Lange attributed the decline of ancient Ghana to numerous unrelated factors, only one of which can be likely attributable to internal dynastic struggles that were instigated by Almoravid influence and Islamic pressures, but devoid of any military conversion and conquest.[10]

Aftermath and Sosso Occupation

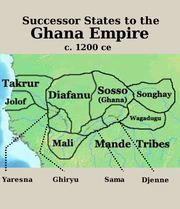

Around 1140, the fiercely anti-Muslim Sosso people of the Kaniaga kingdom captured much of the former empire. Diara Kante took control of Koumbi Saleh in 1180 and established the Diarisso Dynasty. His son, Soumaoro Kante, succeeded him in 1203 and forced the people to pay him tribute. The Sosso also managed to annex the neighboring Mandinka state of Kangaba to the south, where the important goldfield of Bure were located.

Malinke Rule

In 1230, Kangaba led a rebellion under Prince Sundiata Keita against Sosso rule. Ghana Soumaba Cisse, at the time a vassal of the Sosso, rebelled with Kangaba and a loose federation of Mande speaking states. After Soumaoro's defeat at the Battle of Kirina in 1235, the new rulers of Koumbi Saleh became permanent allies of the Mali Empire. As Mali became more powerful, Koumbi Saleh's role as an ally declined to that of a submissive state. It ceased to be an independent kingdom by 1240.

Influence

The modern country of Ghana is named after the ancient empire, though there is no territory shared between the two states. Traditional stories show linkages between the two, with some inhabitants of present Ghana including the Northern Mande tribes like the Gonja. The Akan people also share names and, many cultural attributes of the people of the empire which suggest some history as part of the empire.

Rulers

Rulers of Awkar

- King Kaja Maja : circa 350 AD

- 21 Kings, names unknown: circa 350 AD- 622 AD

- 21 Kings, names unknown: circa 622 AD- 790 AD

- Kind Reidja Akba : 1400-1415

Soninke Rulers "Ghanas"

- Majan Dyabe Cisse: circa 790s

- Bassi: 1040- 1062

Rulers during Kaniaga Occupation

- Soumaba Cisse as vassal of Soumaoro: 1203-1235

Ghanas of Wagadou Tributary

- Soumaba Cisse as ally of Sundjata Keita: 1235-1240

Bibliography

- Mauny, R. (1971), “The Western Sudan” in Shinnie: 66-87.

- Monteil, Charles (1953), “La Légende du Ouagadou et l’Origine des Soninke” in Mélanges Ethnologiques (Dakar: Bulletin del’Institut Francais del’Afrique Noir).

- Expansions And Contractions: World-Historical Change And The Western Sudan World-System 1200/1000 B.C.–1200/1250 A.D.*. Ray A. Kea. Journal of World Systems Research: Fall 2004

References

- ↑ Mahmud al-Kati, Tarikh al-Fettash, mod. ed. and French tr. Octave Houdas and Maurice Delafosse, (Paris, 1913, reprinted Paris, 1964), p. 76. The recension of the MS edited in 1913 was the work of al-Kati's grandson, Ibn al-Mukhtar in the mid-seventeenth century. However, this piece of information surely dates from al-Kati's original MS and his informant probably lived in the mid-sixteenth century.

- ↑ Tarikh al Fattash, French p. 78.

- ↑ as-Sadi, Tarikh as-Sudan, mod. ed. and French translation, Octave Houdas(Paris, 1898-1900) and English translation, John Hunwick, Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire (Leiden, 2003), p. 14, see also fn 5.

- ↑ Maurice Delafosse, Haut-Senegal Niger (Paris, 1912).

- ↑ Nehemia Levtzion, Ancient Ghana and Mali (London, 1973).

- ↑ Prehistoric Origins of the Ghana Empire

- ↑ Chu, Daniel and Skinner, Elliot. A Glorious Age in Africa, 1st ed. Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1965

- ↑ Ancient Ghana

- ↑ Masonen, Pekka; Fisher, Humphrey J. (1996), "Not quite Venus from the waves: The Almoravid conquest of Ghana in the modern historiography of Western Africa", History in Africa 23: 197–232, doi:10.2307/3171941, http://jstor.org/stable/3171941. Available here

- ↑ Lange, Dierk (1996). "The Almoravid expansion and the downfall of Ghana", Der Islam 73, PP. 122-159

External links

- African Kingdoms | Ghana

- Empires of west Sudan

- Empire of Ghana, Wagadou, Soninke

- Kingdom of Ghana, Primary Source Documents

- Ancient Ghana — BBC World Service

|

||||||||||||||||||||